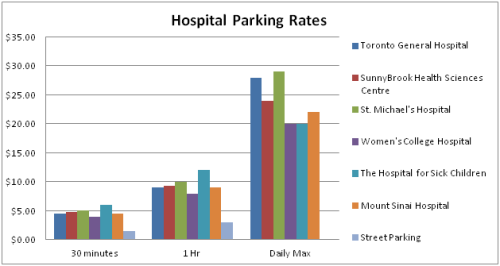

We can see that parking policy should be developed in partnership with patients. Hospital visiting hours are a similar issue. We can trace some of the changes in patient-oriented policy as hospitals become more patient-friendly by looking at policies about visiting hours.

In the early days of the modern hospital, visiting was discouraged. In the comprehensive manual from 1913, The Modern Hospital, the authors are very clear:

We may begin with the flat argument that it would be best for all sick people if all visiting could be prohibited and it is a recognizable situation in nearly every hospital that has visiting days that the temperatures are higher at night on the visiting days than at other times, all else being equal, and this is due to the excitement caused by visitors, not alone one’s own visitors but those who come to see other people…

In considering the visiting question, therefore, we have two or three fundamental ideas in the foreground; one of them is that we ought to restrict visiting as much as possible and we ought in any event to limit visits to the one patient whom visitors come to see. And visits should be as short as possible and whenever it can be done each patient should be restricted to one or two or at least a minimum number of visitors. (Hornsby, Schmidt 490)

In the old days, visiting hours varied by class of patient. Charity (free) patients had severely restricted visiting hours, often limited to a few hours every week. For example, visiting hours for the Children’s Department are listed:

Large (free) wards, 2 to 4 pm Wednesday and Sunday

Small (private ) wards: 1 to 8 pm daily

Private rooms: without other limitations than the order of attending physicians. (Hornsby, Schmidt 340)

Times have changed. Today there is a recognition that patients can benefit from visits, and typically visiting hours have been much extended. Nonetheless there are usually restrictions imposed that vary widely from unit to unit. Restrictions can make things difficult especially if one is trying to stay to support an elderly relative or stay close to a very sick friend.

A recent article in the New York Times describes the view of the Institute for Patient and Family Centred Care (IFPCC) which is to lift all restrictions on visiting hours. They point out that, increasingly, families and those close to patients can play a crucial role in their care. Beverley Johnson, the President of the IFPCC says, “People should go to a hospital with a family member or trusted friend to be an advocate, to ensure continuity, to answer questions and prevent errors.” The article in the New York Times goes on to explain that,

Because she was with her centenarian mother in a Florida hospital, for example, she could explain to a doctor who had never met either of them that that no, her mother did not have a pacemaker, and perhaps he had confused her with a different patient. (Span para 8)

The IFPCC argues that if hospitals do want to partner with patients and their families, it will be important to begin to lift restrictions on visiting hours as a matter of policy. As Johnson says, “You can’t partner with families if you’re locking them out of the hospital, especially when patients are most vulnerable” (Span para 4). We agree that policies about visiting hours should be reviewed with this in mind.

Hornsby J, Schmidt R. The Modern Hospital. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: W. B. Saunders Company; 1913.

Span, Paula. “A Move to Extend Visiting Hours at Hospitals.” The New York Times. Web. 11 July 2014.